This paper has been published by Sage Publishing—a Thomson Reuters company.The focus of this paper is on gamification and how massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG) aid in language learning. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516665105 (opens in new window)

Gamification and Game-Based Learning

(partial)

Abstract

In the last 10 years, gaming has evolved to the point that it is now being used as a learning medium to educate students in many different disciplines. The educational community has begun to explore the effectiveness of gaming as a learning tool and as a result two different ways of utilizing games for education have been created: Gamification and serious games. While both methods are used to educate, serious games are meant to provide training and practice without entertaining; whereas, gamification uses game-like features such as points and similar to serious games is not meant to entertain. This review will provide an overview of gamification and serious games as well as the learning possibilities of non-educational games such as massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPG). Finally, MMORPGs will be discussed in detail as to whether they can meet the general behavioral requirements of effective learning.

Keywords: MMORPG gamification, gamifying, cultural heritage and gamification, culture and gaming, role playing games and language

Gamification and Game-Based Learning

Video games have become a very serious business as a form of entertainment. It is no wonder that so many people play games on a regular basis. As a matter of fact, 17 percent of the world’s population is involved in playing games (Kim, 2015b). In addition to playing games for entertainment, says Kim (2015b), a new use for games has emerged within the last 10 years and it is called gamification. Gamification is a way to use game elements to learn, but without the entertainment value (de Byl, 2013). Gamification strives to take the best parts of video games such as awards, badges, etc. and apply them to pedagogy. In addition to gamification, serious games have also been created to educate but in a different way. According de Byl (2013), serious games are used to practice, train and provide solutions. Many different versions of serious games do exist, and some are meant to make boring, everyday tasks a bit more interesting. For example, SwarmTM allows people to share their location with people on their social network as well as being rewarded with coins on a leaderboard for checking in at different places (Aguilar, 2014; Crook, 2015). There is a new type of game that has entered the gamification arena called MMORPG. While gamification is not based on entertainment, MMORPGs are very much entertainment based and are being evaluated to determine their effectiveness in learning languages (Ryu, 2013). MMORPGs such as Everquest™, World of Warcraft™, and various other games, says Ryu, engages players in the sense that learners who played the game with native speakers understood more vocabulary items and communicated in a manner that was both collaborative and social in nature.

(excerpt)

Video Game Characteristics

According to Kim (2015b), there are four characteristics of a video game: (1) a system that provides feedback, (2) the goal, (3) the rules, and (4) voluntary participation, and these characteristics are present in gamification, though, not as profoundly. Gamification is a great way to take mundane activities, such as shopping at the super market, and make them more interesting. SwarmTM is a gamification mobile application (app), and a FoursquareTM offshoot, that launched in 2014 that allows its users to create social networks in order to track down their friends as well as do check-ins and share their location (Popper & Hamburger, 2014). Additionally, when users check in to a place often enough they can earn stickers (see figure 2) to apply to check-ins to express how they are feeling, earn coins that are displayed on a leaderboard (see figure 3), and they can even become Mayors (Crook, 2015).

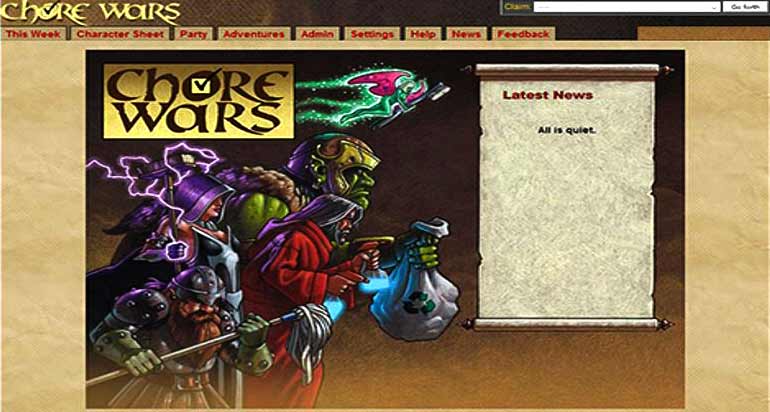

Another task that has been gamified to make it more interesting is called Chore Wars (see figure 4). Chore Wars™ allows members of a particular household, or even a workplace, to compete doing everyday tasks such as cleaning the house, shopping for groceries/office supplies etc. and earn points, increase in level, and earn game gold which can then be exchanged for actual rewards based on how the game is set up (Kim, 2015a).

Figure 4